A Brief History of Iconic DIY Indie-Pop Label Sarah Records

- Avery Luke

- Jan 22, 2021

- 9 min read

"Sarah Records is owned by no one but us, so it's OURS to create and destroy how we want and we don't do encores. We want to burn in bright colours and go pop, to be giddy, impulsive and silly, to kiss people in new places— EXQUISITELY— and DARE to tear things apart. The first act of revolution is destruction and the first thing to destroy is the past. Scary. Like falling in love; it reminds us we're alive."

— Sarah Records 1987-1995

Clare and Matt (founders of Sarah Records), 2003

Sarah was a Bristol-based independent record label founded by Clare Wadd and Matt Haynes, active between November 1987 and August 1995. Sarah existed on the fringes of the music industry and modern culture— its idiosyncratic sound and aesthetic represent the idea that music can thrive in a connected community without the help of the industry or business strategy. Sarah brought together fans and artists through curated zines, letters, and single albums and created a lively following that remains enthusiastic about the label today.

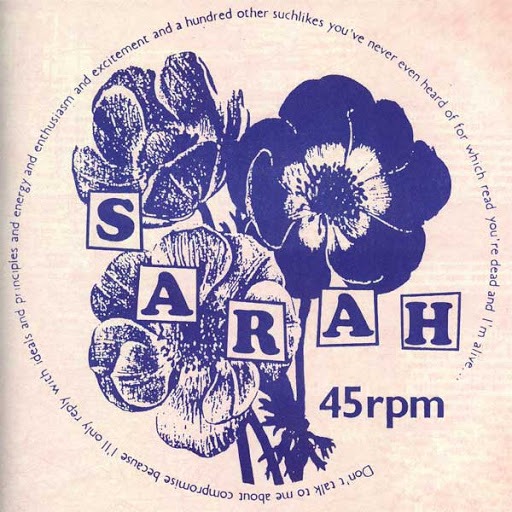

Sarah’s unconventional label model is most evident in the way its releases were structures. Sarah’s most iconic discography included 100 singles that were often accompanied by inserts that were handwritten by Clare and Matt, or read like a diary entry. Before Sarah, Clare and Matt each had their own respective zines, so the spirit of the “fanzine” inspired so much of what Sarah Records did and made an impact on the music, too. Zines were significant enough to Sarah that they were included in the discography and given catalog numbers as if they were a single release.

Insert for Sarah 60 which accompanied a single

by the artist Another Sunny Day.

Clare's zine Kvatch and Matt's zine Are You Scared To Get Happy?

“A really well-written fanzine should have the same effect on you as listening to a 7” single. You read 10 pages in a fanzine and it should make you feel the same as listening to 3 minutes of a pop song.” — Matt Haynes, "My Secret World: The Story of Sarah Records"

In the eighties, fanzines were much more than a creative or aesthetic endeavor. When fanzines were passed out at indie “gigs,” they were in high demand for their informative value, too. With virtually everything else on the radio (aside from John Peel) being only music from major or large independent labels, a younger generation of alternative listeners had to be inventive in their music discovery.

Radio DJ John Peel broadcasting in 1981

Zines often included a lot of personal writing, visuals, and other creative elements separate from the music featured. Sarah zines were appreciated for their particularly intimate writing— Clare and Matt were dating at the time, and some of the writing would even include elements of their relationship. Ultimately, the zines read like a Sarah Records diary of sorts, and it made listening to the music even more special.

"The idea is that you don't have to go along with a corporate idea of what music should sound like— you can do your own thing, you can be adventurous, you can be imaginative." — Matt Haynes.

Sarah 004 fanzine, 1988

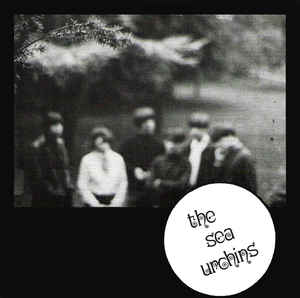

The band that initially brought Clare and Matt together to collaborate as Sarah Records were The Sea Urchins. At first, The Sea Urchins were perceived as being a little bit more of a cool and silly “clique” than a legitimate artist to watch. However, after an eccentric show in Bristol, Matt and Clare were impressed. Sarah’s very first single was Pristine Christine by the Sea Urchins released in 1987. It got a fantastic response and was even played by John Peel on the radio, which was delightfully unexpected for Sarah’s first-ever release.

The Orchids’ I’ve Got A Habit was Sarah 002, and they stayed with Sarah for the full duration of the label’s existence, releasing five singles for the label— the last being Thaumaturgy, Sarah 66. The third single released on Sarah was Anorak City by Another Sunny Day which sold out 1500 copies via flexi-disc— this is when Sarah really began to press forward their sound by bringing in more artists that featured some fuzzy guitars and rock elements. Even this early on in their discography, Sarah was gaining significant attention with radio-play from John Peel and growing listeners in the indie-pop community. Even early on, Sarah had a major voice in the underground music scene.

"You were either left-wing or right-wing and a lot of people were very vocal about it. That was the backdrop to the scene Sarah existed in and we were both very interested in politics."

— Clare Wadd.

One major reason why Sarah aimed to preserve the 7-inch limited release singles format was due to the label’s aversion to capitalism. Clare and Matt were interested in music politics and in their view, a lot of record companies were trying to rip off consumers by having them buy multiple releases that felt like the same thing— “limited editions” are cited by the pair as being one example of an often gimmicky marketing strategy.

Sarah aimed to counter this system by making their records more limited and valuable; seeing things from the fans' point of view both economically and sentimentally. Vinyl releases were important to Clare and Matt too, because CDs were expensive at the time and represented a lot of major labels wanting consumers to "re-buy their entire record collection." Making collectible singles seemed much more sincere and realistic for the small label to pull off.

Insert in Sarah 070, 1993

Sarah wasn’t politically shy in how they presented the label, either— both in writing and in music. Clare and Matt were very outspoken about issues surrounding feminism in the music industry. Later on in Sarah 70, an insert is collaged with statements like "So what if it's a great POP single, it's still girl-sings-while-boy-plays-guitar and it's still released on a label run by a man (and what was that about seizing means of production?)" and "I want to be interesting because of myself, not because of what some man did to me."

The Field Mice performing in Birmingham, UK, 1988

Sarah 012 in 1988 would become one of the more significant releases for the label because it marks the beginning of The Field Mice’s involvement with Sarah Records. Emma’s House has a bedroom-recorded feel, but also exemplifies Sarah continuing to evolve their sound from quaint pop music— it has a steady beat and is often referred to as being similar to some new-wave dance music at the time, like New Order.

"Before Emma's House came out, we'd only been playing for about 3 months, 4 months... not a long time. There were a lot of different sounds going around at that time... it was the start of grunge... There were a lot of different influences around and we were never thinking 'We mustn't listen to that.'"

— Michael Hiscock of The Field Mice.

The band was young at the time and grew both personally and musically during their time at Sarah Records. "Before Emma's House came out, we'd only been playing for about 3 months, 4 months... not a long time," said Michael Hiscock of The Field Mice. "There were a lot of different sounds going around at that time... it was the start of grunge... There were a lot of different influences around and we were never thinking 'We mustn't listen to that.'"

Their second single, Sensitive (1989), is often cited as being the most successful and memorable— the single reached number 12 in March of that year which was a significant milestone for the band. The Field Mice only stuck with Sarah for a few years, in light of some conflict within the band.

The Field Mice’s breakup was emotional, and this was evident in the solemn energy of their latter performances. At their very final gig, they played all new songs and refused to look at or speak to each other. The Field Mice’s Missing The Moon was their final release for Sarah, despite being on the path to success. Following the breakup of the Field Mice, Bobby Wratten formed the synthy-er Northern Picture Library with two other members, and they had singles that were released on Sarah’s very late discography.

The Field Mice at Denmark Hill Station, 1991

Another significant artist for Sarah was The Wake, a band from Glasgow, Scotland that formed in 1981, originally signed to larger label Factory Records. In light of a somewhat contentious relationship with Factory towards the late eighties, the band reached out to Sarah in 1989. This was a somewhat surprising and exciting addition to the Sarah lineup, given that this band was already well-established and excited about working with an intimate label as Sarah. The single that The Wake put out for Sarah, Crush The Flowers, was a fitting addition to Sarah's discography despite not having recorded it specifically for Sarah; it meshed well with the label's energy. The Wake worked closely with the Field Mice as well, and both are thought of as especially significant artists on the label.

Carolyn Allen of The Wake

“The idea that anyone can start a fanzine, anyone can start a label… that was the bedrock that [Sarah] was founded upon.” — Clare Wadds

A negative review of St. Christopher, NME

Despite having such a strong and devout following, Sarah was essentially universally disliked by the music press and received much negative feedback. “Twee” carries less of a negative connotation today, but during this time it was used as an insult to Sarah in both the music itself and how the label presented itself. This can partially be attributed to the aesthetic of edginess that was so trendy in Indie-rock music at the time. Additionally, music journalists didn’t like Sarah Records because they represented the antithesis of traditional music norms and defied expectations for artist success and label operations. Sarah Records was also outspoken about its opposition to the press and condemned music journalists for their lack of passion. Much of the negative press was centered around sexism as well, and even well-intentioned reviewers would simply reduce Clare to “Matt’s girlfriend.”

Photo of Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill in 1994

"I felt really called to have a female reference because there were so few female references in the music industry at the time. Everything was so male-orientated whether it was the press, the record labels— just everybody in positions of power in the industry was male, so we liked the idea that this label would come along and it would have a girl's name essentially." — Matt Haynes

Sarah 30 was Heavenly’s I Fell In Love Last Night.” Amelia Fletcher, who was previously a member of the successful act Talulah Gosh, was the frontwoman and sole songwriter. Talulah Gosh had broken up earlier, despite being an influential and successful act in the indie-pop scene. Clare and Matt, having been big fans of Talulah Gosh, were eager to put out a record for Fletcher’s new project. Part of what made Heavenly so distinctive was how the band presented their femininity. Amelia Fletcher was neither a background act nor came off in a particularly sexual way. Heavenly, especially early on, was light, fun, and feminine pop music.

inspired by the political-punk Riot Grrrl movement in music. Fletcher also had some connections to K Records in Olympia, Washington who were largely involved in the Riot Grrrl movement. It was around this time in 1991 that K Records was putting together the “International Pop Underground Convention” which was a festival that featured femme punk acts like Bikini Kill. Heavenly brought in some elements of this punk rock into their later releases. This punkier sound can be heard in Sarah 51, Heavenly’s So Little Deserve, but they never lost their pop sound completely, making for a special melding of genres that fans appreciated.

Heavenly, taken for an article in Japan

NME review of single Atta Girl

Today, Sarah is often remembered for being “twee pop” and was thought of as representing only that sound at the time. However, it would be unfair to pin Sarah into a particularly niche genre, given that the label had intricate projects that breached beyond the barriers of simplistic pop. For example, the band Shelley (who released Reproduction Is Pollution on Sarah 98), took great inspiration from upbeat dance music, and The Harvest Ministers included string instruments on some of their discography as well.

Perhaps the reason Sarah is mistaken for having such a narrow sound is that it was so cleanly curated outside the music itself, meshing individuals together as a greater collective. Despite bands having sounds that ranged from shoegaze to pop-punk and everywhere in between, Sarah maintained its ironic ethos of pop music that sounded quiet and “twee” but had rebellious undertones of rock.

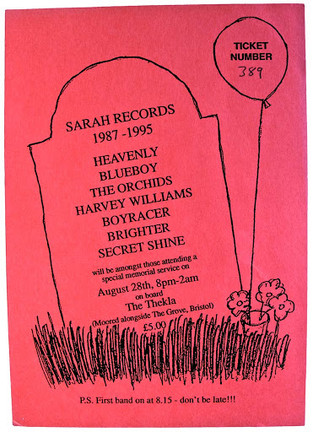

Ticket to Sarah 100 party

Sarah 100 marks Clare and Matt’s deliberate and iconic end to the label. As the one hundredth catalog number was coming up, it was marked as a surprise— but no one could have anticipated that the label would choose to end itself in its prime. A compilation CD and booklet were released (There And Back Again Lane, Sarah 100) and a final party was announced that would take place at The Thekla— a venue in Bristol on the harbor. The event, which was open to fans and artists alike, was somewhat bittersweet given that it was known that this was a definitive end. Sarah’s end was truly mourned like a death, given that the label had evolved into such a lively force for connection and emotion through music.

Advertisement for A Day for Destroying Things, Sarah 100

Today, Sarah Records is appreciated for its contribution to the music scene in the late eighties and its early nineties, and for the impact its ethos has on the industry and greater community today. Sarah singles are incredibly sparse and treated as collector's items. The “do-it-yourself” spirit of Sarah inspires a lot of what we see in today’s up and coming music projects. The label itself was a work of art, rather than a tool of the industry. Sarah Records shows us that anyone who is passionate about art can share in the scene, and create something beautiful to do anything they want with, even if that means destroying it with pride.

This history of Sarah Records truly captures the spirit of indie music and DIY culture. It's fascinating how the label not only embraced unique sounds but also built a loyal following through authentic connections. In a similar way, seo outreach helps businesses build genuine relationships and expand their presence online. By reaching out to the right people and engaging with them authentically, like Sarah Records did with its audience, you can elevate your brand and reach a wider community. This post beautifully showcases how staying true to your roots can make all the difference in achieving long-term success.

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.